Two hours to midnight January 13,2014.

Colombo bound ‘Red-eye’ flight from a Gulf state is on the runway.

Among the full compliment of international passengers were many Sri Lankan female migrant workers.

The plane was readied for take off, belts buckled up, cell phones, ipads and laptops powered off, seats held upright, lights dimmed and cabin doors closed.

The pregnant silence that ensued was suddenly broken with an ear-splitting shriek in Sinhala:

“ Take me off this plane. I want to get off. I don’t wish to fly “ screamed a young woman in her mid-twenties. She stood at the middle of the aisle in animated exasperation.

Fellow workers identified her as a compatriot returning home after a stint in Beirut.

Concerned cabin crew rushed to calm her down, but in vain. She went ballistic, blurting out disjointed sentences: ‘ I want .Money , Money, …. Salary…..” etc.

When the hyperventilating lady entreated other passengers also to get off the plane thus causing a slight panic, the airport security staff moved in politely to escort her out of the aircraft.

The flight took off and landed in Colombo safely, one hour behind schedule.

The vexatious episode initially reminded me of Mr. T of the eighties Telly drama ‘ A-team ‘ who had to be sedated into an aircraft due to his fear of flying.

But Pteromerhanophobia (fear of flying that is) may not have been the case here as the lady had already flown out when she went for employment abroad.

Understandably like many migrant workers in the Middle East she may have been a victim of a stress, depression and anguish, which could have triggered off a confused state of fright.

Sadly, she is one of the precious migrants who help earn billions of dollars to boost Sri Lanka’s coffers.

At the last count wasn’t it US$ 7 billion in 2013?

It is a paradox.

This rather disquieting little interlude on that night flight sheds light on a much larger syndrome.

The plight of domestic workers in the Middle East is nothing new. Nobody is unaware about it.

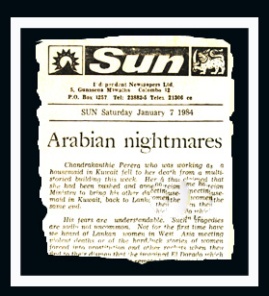

For instance thirty years and one week to the day the once dominant but now defunct SUN newspaper editorialized their plight under the headline “ Arabian Nightmares’. (See Flashback clip).

The editorial followed the death of Chandrawathi a domestic worker who leapt to her death from a multi story complex in Kuwait.

Citing a plethora of horrifying incidents of violence, trafficking and abuse the SUN urged the authorities to set things right and seek resolution to this detestable situation.

Needless to say, successive regimes have taken some praiseworthy steps down the years. But their best has not been good enough.

If laws and regulations as well as enforcement were in good stead, underaged worker Rizana Nafeek would not have been beheaded. The crooked traffickers who fudged her real age must hang their heads in shame.

If labour agreements enshrining worker rights were mutually negotiated with host countries, L.P. Ariyawathie would not have had 24 steel nails skewered to into her body by a ruthless employer who makes Marquis De Sade look a mere naughty novice.

While Sri Lanka reaps benefits by way of remittances that help boost its GDP, host countries are bigger beneficiaries with the cheap labour.

Domestic migrant workers are typically poor and economically destitute. Lured by fancy promises they seek greener pastures. They are innocently oblivious to the horrendous conditions that await them. Some come unscathed and some are lucky too with ethical, decent and honest employers. But they are just handful. Others grin and bear the suffering for a pittance they earn that is still better that what they could get back home.

They are ready to forego their dignity, leave alone access to justice. Except for a few concerned groups of rights advocates, the political will to make decisive changes in the migrant labour market and improve the lot of workers during the past three decades have been lackluster if not gossamer thin.

Poor women in quest of illusive fortunes while escaping poverty at home, invariably fall easy prey to traffickers posing off as local agents who operate hand in glove with crooked foreigners.

These workers are absolutely ignorant of rules and regulations that await them in host countries. There have been instances in the past when vulnerable women were lured into jobs that never existed. Some were forced into veritable slavery. Regular reports in the local media have cited instances of physical, mental and sexual abuse they suffer.

In recent times the Foreign Employment Bureau has stepped in to educate, advise and train prospective workers in a bid to minimize exploitation. That is a step in the right direction. But it would also be good if the workers and their families they leave behind were closely monitored at village level to eliminate the various social ills and deprivations that follow migration.

The recently concluded labour agreement with Saudi Arabia is timely and laudable as it could provide certain important safeguards to migrant workers.

One of the main sources that facilitate worker exploitation in the Middle East is what is known as ‘Kafala’ system that exists in the Middle East. It’s a legal ‘sponsorship’ facility whereby the sponsor could ‘own’ the worker; being responsible for visas and every legal status of the employee including her wages.

The sponsor could also transfer the worker to anyone under this scheme. Arguably it facilitates human trafficking.

It is globally decried as being ultra vires international labour laws, and against a pertinent provision in the Universal Human Rights Declaration.

Two years ago Bahrain was liberal enough to get rid of this system while Kuwait is reportedly contemplating in doing so. Hopefully others will follow suit.

Yet, with an age-old psyche and culture of enslavement that prevails, change seems to be rather slow in coming.